1967 Centennial Stamps

Definitive Stamps, Fluorescence, Paper & Tagging

1967 Centennial Definitive Stamps:

Presented by Hank van der Linde

First issued in February of 1967 to commemorate Canada's Centennial, this rather innocent group of 12 different denominations has grown to 16 different values with an almost endless list of minor and major varieties. From single stamps to booklets to Stationery and the special Centennial Philatelic items, this Issue has come to both challenge and intrigue collectors. There was also a new series of Postage Due issued. Actually it drives many collectors nuts! From different gums to different types of papers to levels of fluorescence, to types of tagging, Canada Post with its’ various experimentation has unknowingly created a philatelic nightmare that will see the ink continue to flow on these Issues for years to come. Almost 50 years have passed since those original 12 stamps were issued and yet we are still finding new varieties.

The purpose of our presentation is to give you a flavour of the issues collectors face. Unfortunately we do not have definitive answers.

The Centennial definitive series issued on February 8, 1967 consisted of twelve stamps. The five lower denomination stamps featured the image of Queen Elizabeth combined with a

regional view of Canada. The five geographical regions of Canada, the North, the Pacific Coast, the Prairies, Central Canada and the Atlantic Coast were represented in succession from the one

cent to the five cent denomination.

The seven higher denominations (8ȼ to $1.00) featured famous paintings of Canadian scenes by Canadian artists including Tom Thompson and some of the Group of Seven.

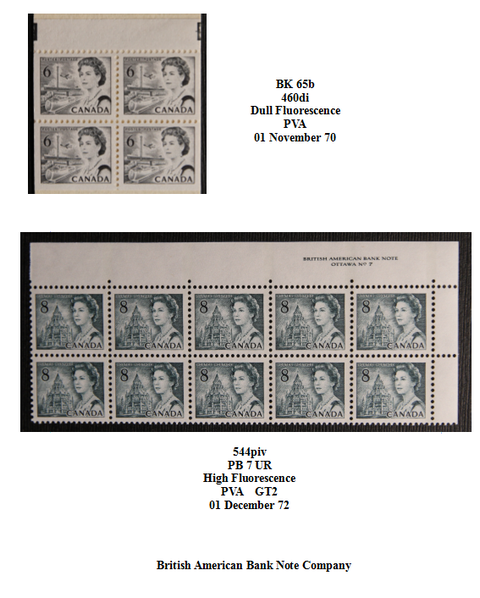

In subsequent years (1968 – 71) additional denominations were issued; 6ȼ orange – 1968, 6ȼ black – 1970, 7ȼ green - 1971 (all transportation design) and the 8ȼ Parliament – 1971 with the result that there are sixteen designs in total.

The initial release on February 8, 1967 included three coils (3ȼ, 4ȼ and 5ȼ). Subsequently four additional coils were issued (6ȼ orange, 6ȼ black, 7ȼ green (all transportation design) and the 8ȼ Parliament)). That brings the number of individual stamps collectors need to complete their collections to 23.

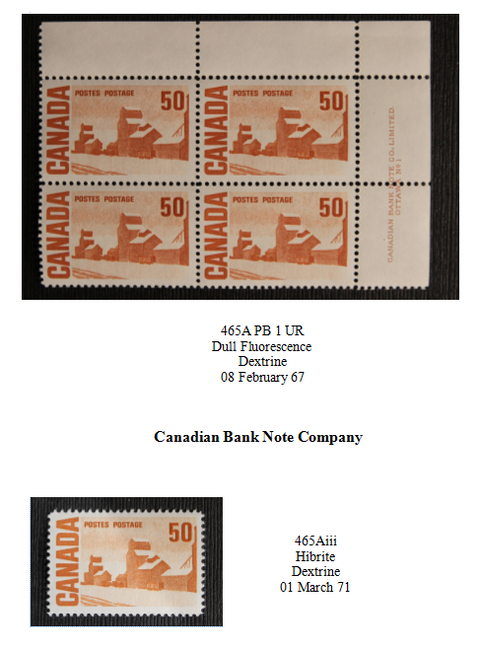

In addition to the coils, the lower denominations (1ȼ to 8ȼ (the Parliament issue)) were also issued as booklets and in some cases as miniature panes. During the period that these definitives were current, there were two different companies (Canada Bank Note Company and British American Bank Note Company) that printed these stamps as booklets as demand necessitated. That created another 12 different stamps collectors needed to complete their collections. Now we’re up to 35 in total.

But CPC didn’t stop there, there were differences in perforations when the booklets were printed. The initial issues of February 8, 1967 were perfed at 12. Subsequent issues were perfed differently; 6ȼ orange was 10, 6ȼ black, 7ȼ green and 8ȼ Parliament were 12.5 x 12.0 while the coils of those denominations were 10. The booklets were 10, 12 or 12.5 x 12.0. These perf variations added another 3 stamps to what collectors needed to complete their collections.

The 6ȼ black also had a couple of die differences which increased the number of stamps by 1 for a total of 39 different ones to be collected.

For the Inscription Plate Block collector, life also became more complex as there were 49 different plates in total for the various issues between 1967 and 1971.

Stamp collecting was further complicated by CPC when it decided to tag the definitives to allow for automatic cancelling equipment to speed up the handling of mail. There are 30 issues in this series consisting of W1B, W2B, WCB, GT2 and OP4 tagging on regular issues as well as booklets and coils. The use of an ultra-violet light is helpful in identifying the various taggings. It should be noted that there are a few varieties within these taggings such as the width of the tagging

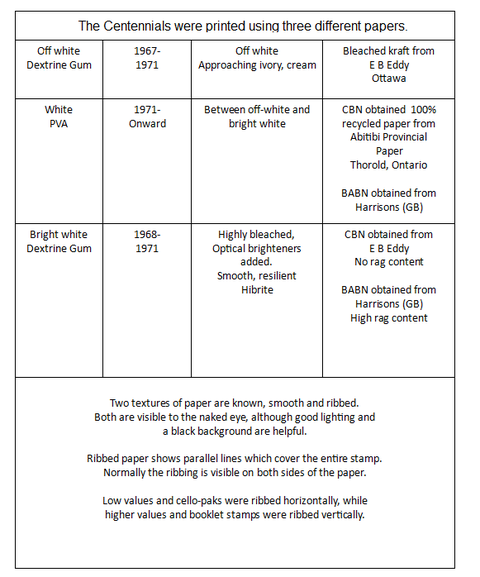

One further complication is gum. For the collector of used or cancelled stamps this is not a problem. But for the collector of mint stamps, it increases the number required to complete the collection. Initially the gum used was dextrine which is a shiny yellowish colour. This was replaced in 1971by PVA gum which is almost invisible and colourless.

Have you lost track of the number of different stamps a collector needs to have a complete collection?

Did I mention that there are also several varieties and errors? I won’t go into that at this time. I think that there are more being discovered from time to time.

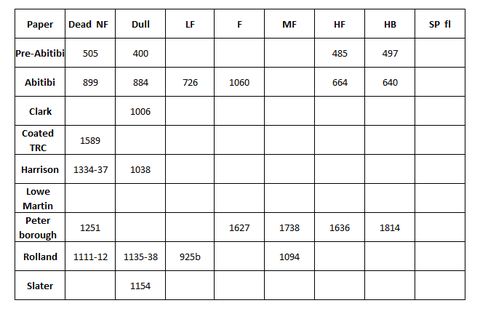

A further complication that collectors confront is the type of paper on which the stamps were printed. Initially they were printed on plain paper. In 1968 and subsequently different papers were used with varying degrees of whiteness. They range from hibrite (HB), high fluorescent (HF) to no fluorescence (NF) and several degrees of fluorescence in between. This is an area that drives collectors over the edge.

Fluorescence, Paper & Tagging

Presented by John Morrell

Paper and Paper Making

The earliest papers were made from hemp –

dating back to about 100 BCE. During Medieval Europe paper evolved through

the Middle East Corridor sometime between 1200 and 1300 AD. And with the

invention of the printing press, paper became more and more sophisticated. However, the paper making process has remained virtually unchanged for several centuries.

Some papers, those used for money, stamps and stationery, can be made from linen, cotton, flax, hemp, bamboo and other grasses. Latex papers can contain both cellulose and synthetic fibre. While it can be made from a host of basic materials, almost all of the paper today is made from wood fibre.

To make paper wood is first turned into pulp by disintegration, a soup of cellulosic wood fibres, lignin, water and some chemicals used in the pulp process. Around the time when the Centennials were being issued they began employing a chemical to separate the lignin from the fibres. They were discovering that lignin weakens the bond between the fibres themselves. It also lends potential discolouration to the paper. Once separated the fibres can then be bleached or coloured to produce the desired end product.

At this point the pulp mixture is set onto a mesh screen and formed into a layered mat. The mat is squeezed to remove the water and then dried. Then the mat is run through heated rollers and compressed to remove any watery remains and wound onto large continuous rolls. The paper might then be cut or transferred into customized sizes to meet the specifications of the users.

Additives may be mixed into the pulp and/or applied to the paper web later in the production process. The paper may also be ‘sized’ with fillers such as chalk or china clay, which improve the characteristics for printing or writing. The purpose of sizing is to establish the correct level of surface absorbency to suit the ink or paint or to otherwise alter its physical properties for use in its intended application.

At this stage the paper is considered uncoated. However, uncoated papers are rarely suitable for print screening above 150 lines per inch, (lpi). Coated papers are treated with a compound or polymer to add weight, gloss, smoothness or ink absorption. If it is to be coated, it would receive a thin layer of material such as calcium carbonate, kaolite or china clay applied to one or both sides to create a more suitable surface for high resolution half tone screening. If a smooth high gloss surface is required, both uncoated or coated papers might be ‘polished’ by a process called calendaring. For paper intended as stamp material other ingredients might be compound formulated to add wet strength and/or UV protection.

In 1878 E. B. Eddy patented a process for the production of mechanical pulp. He set up his first mill on Philemon Island to supply indurated fibre for pulp paneling. In 1882, fire destroyed all of his establishments. In order for him to secure financing to rebuild, he was compelled by the major stakeholder to employ the banks key administrator, William Horsley Rowley, who would, in fact, remain one of Eddy’s most trusted employees through 1915.

From matches and lumber, Eddy was able to foray into paper making by inventing a vertical pulp digester. His first paper was muslin, resembling silk or tissue. Gradually he progressed through a variety of paper making processes and by 1896, Eddy was producing white paper and newsprint. By 1902, Eddy was manufacturing more than 70 varieties of paper product. E B Eddy was a major supplier of paper to the Canadian Bank Note Company for their Centennial printings.

From its founding 04 December 1912, Abitibi Power and Paper Mills Limited was among the largest producers of paper in the world. Abitibi Provincial Paper supplied recycled paper to the Canadian Bank Note Company for the production of all of their stamp issues from 1971 onward. From 1972 to 1983 Abitibi was the sole supplier of paper to Canada Post. However, in 1983 Abitibi decided to discontinue its paper line from which stamps were being made forcing CP to obtain its papers from other sources. In 2008, Abitibi decided to close its operations in Newfoundland Labrador, prompting the NL Government to expropriate all of the holdings of the company in that Province.

In 1795, Robert Scot, the first official engraver of the United States Mint, founded the American Bank Note Company. ABN was the official printer for Canada’s first issue in 1851. They printed the majority of Canadian stamps between 1879 and 1911, including the Jubilees.

Canada’s earliest stamps were printed by the American Bank Note Company and the British American Bank Note Company. BABN was founded in 1866 by a group of printers and engravers and at the time of Confederation it was the first bank note company in Canada. In 1923 ABN would become the Canadian Bank Note Company. Until it was sold to Canadian Bank Note in 2013, BABN was entirely owned by Canadians.

CBN and BABN were the major printers of all the Centennial stamp issues.

CBN Fluorescence

BABN Fluorescence

Centennial

Papers

Fluorescence

Tagging

Tagging began with the Wilding Issues, 13 January, 1962. Canada Post was introducing some facer cancelling equipment, for which tagging was expected to facilitate the process. Phosphorescence was chosen for the original tagging but unlike fluorescence, a phosphorescent material does not re-emit the radiation it absorbs at the same intensity. And it takes longer to become excited because it absorbs its radiation more slowly.

W1B – Winnipeg 1-Bar – a single bar usually along one edge of the stamp.

W2B – Winnipeg 2-Bar – tagging bars at both edges of the stamp.

WCB – Winnipeg Centre Bar – a single bar usually through the centre of the stamp.

These tagging bars were can be found in a variety of widths.

Winnipeg tagging was used until 1972, when it was replaced by a fluorescent type, a so-called General Tagging, OP4. OP4 was very problematic and it was eventually found unsuitable because of its migratory qualities. After a brief period of testing, in 1973, OP2 became the tagging of choice and remains to the present time.

Some stamps are still produced untagged. These are mainly low and high value definitives and some stylish stamps used today.

Ottawa Philatelic Society

Ottawa Philatelic Society